Palisade Nuts and Bolts; the Nitty Gritty

Life goes on. With just a few weeks passed, memories of the time Ian and I spent up on the Palisade ridge are fading. "Media" coverage notwithstanding, this waning clarity is consistent with the experience we sought. We tackle these things for the moment. The type of moment that climbers like Ian and myself seek is high exertion, deep uncertainty, complex challenge, and management of hazards acute and subtle. We describe that moment, anticipate the moment, rehash the moment, but more than anything, we live the moment.

Slovenian alpinist Marko Prezelj describes what he calls a "classic dilemma of modern adventure activities." When in the mountains with our cameras and satellites and sponsors and agendas are we "'living the moment' or 'capturing the moment'?" To be moving forward into life after an experience that one has described as "one of the greatest American mountaineering achievements" (whoa, exaggerate much, Bela?) is reassuring. I can't speak for Ian, but I constantly wrestle with my own motivations. Am I tackling these things in the peaks for recognition and accolades? Or for more "pure" rationale? The contentment I feel with taking on the rest of life confirms, to me, that the real value of our Palisade Traverse was in the moment; the opportunity to dig deep and work hard. Truth is, writing up any sort of logistics post has been directly requested a few times. And it's like pulling teeth to find the motivation to lay it down here. But here it is, this one's for you.

There are pictures and fluffy news articles out on the web now. I'll let you seek that out. There's video of us mumbling, exhausted, to the quirky and dynamic Skandar. I'll let you search that out. And make your own guesses about what, besides 63 lbs of body weight, Skandar might have lost there at 16k in the Karakoram. This post is unadulterated words. Stream of consciousness spray.

We trained like fools. As far back as the vernal equinox 2012, the day the rules changed that year, I can find an exchange between Ian and I. "Let's do something huge [next winter]. Let's pull smart and @&$#ing hard". I quit sugar and wheat for months at a time. Ian ran. I logged weeks on end of 40-60 hours of training volume, and went to the gym on days in town. Ian cut his drinking and body mass by pounds. Ian turned his sacred rocktober into rockandrun-tober. He woke early on normally casual mornings in Indian Creek to bust out intervals. I hear he even ran down bunnies for extra protein. We skied and scratched and post-holed all over the High Sierra through the early winter. We even risked life, limb and core-shot ropes for an obscure, and likely first, ascent.

We put our loved ones through stress. Modern communication technology allows for the option of emergency response in the hills. But Spot devices fail. We had a plan, we had a contingency, we had a contingency to the contingency, we had buy-in from our responsible people out in civilization. But when the Spot failed to deliver the messages we sent for a day, our ladies were not impressed. I have strong feelings about crafting an excellent emergency response plan for those we leave responsible in civilization. That is an entire post of its own, coming up.

We faced uncertainty. Pacing on summer efforts in the Palisades and elsewhere in the range, compared to winter pacing on the same endeavors indicated that the food and fuel we could carry in the Palisades might give us enough time to complete the whole deal. Weather forecasts beyond 5 days (What we determined to be our threshold for self-contained winter climbing of this nature) are not perfect. And we needed perfect weather. Ian did the entire traverse in summer and remembered certain sections as real burly. "What will we do there?" Not to mention all the "normal" issues: We had no extra gear to drop. We had no margin for injury. However, had you asked us beforehand, we'd have asserted that we had no margin for illness.

But we had illness. Ian toughed out some rugged lower gi distress on day 2. Food went straight through. Ian's built like a rail. A tough-as-nails, burly-ass rail. But a rail nonetheless. He gave up empty beer calories and carved pounds off his physique the weeks before. High altitude exertion stripped calories that day 2's poop-fest did nothing to replace. He bonked hard, but climbed harder. The dude wanted it, and has skills to back up the desire.

If Sierra ridges are some of the biggest and baddest around, Ian could very well be the biggest and baddest ridger around. Summer and winter, he's accumulated a ridge-running resume virtually unequalled. And he's not done. Sick f'er was already rattling off big dreams before we finished Agassiz. Its an honor to watch him weave high-level athleticism, skill, logistics and motivation into hard-charging accomplishments. I feel blessed to surf the swells of his perfect storm of ridge-line accumen.

I bring my own unique qualities. The coach in the gym, just today, said "you're real good at breathing." A tough-to-please mentor has pointed out that I "have become efficient in alpine rope handling techniques". I spend more time guiding high and rocky ridges than anyone else, at least here in the Sierra. I pushed limits last summer in the first guided ascent of the complete Evolution Traverse.

We carried very little. A Black Diamond tent sheltered us and the snow-melting stove. A tiny titanium jetboil and 20 oz of pressurized fuel melted snow, boiled water to hydrate meals, and warmed the occasional hot water bottle. We even heated the tent while preparing one morning. We finished with plenty of fuel. We each carried about 1/2 of a standard length foam sleeping pad. We carefully laid out the rope, slings and our backpacks beneath our feet each night. We shared Ian's 2lb Feathered Friends Spoonbill bag. The Spoonbill was clutch. It cut our sleeping insulation weight to about 40% of what it might have been otherwise. That's huge. Had we gone with traditional sleeping bags we each would have carried 2.5 lbs of down and nylon. Because the Spoonbill isn't insulated on the bottom and because we could share some body heat in the shared space, we were super comfortable with a tiny fraction of your standard two person sleep system. I can't recommend the Spoonbill highly enough. We packed it all in matching Cold Cold World Ozone packs. Good luck trying a modern, mass-produced, ultralight pack on a ridge like this. I've seen packs destroyed in a single route, but my Ozone now has 3 big traverses on it. It's about done, but I'm more than psyched with its durability.

Teams on previous attempts carried steel spikes for all eight appendages. That's roughly 8 pounds of steel that they had to put on and off and deploy and stow over and over again. We took a single 8 oz CAMP aluminum ice axe. We tread-milled through firm snow and ice, but didn't ever have to decide whether to spike up or not. Simple minds need simple decision-making. We gambled, and maybe won as a result.

On previous big traverses I've been stoked to carry a short, single-rated rope. 30 or 40m of 9.2 stows nicely over the shoulder, inspires confidence on sharp edges, deploys rapidly, and can be forced into function on most Sierra rappels. An 11th hour decision, aided by our generous contact at Sterling Rope, left us taking along 50m of twin rope. We immediately folded it in half and virtually never used it out of its 25m form. We worked it out, and were thankful for the extra length in a handful of rappels. Much thanks to Tim Richards and Sterling for the better-than-perfect Photon 7.8.

We wore light clothing. Long johns and softshell pants each. I carried lightweight CAMP wind pants and never wore them. We each did our own thing on the upper body. I wore a t-shirt, an OR fleece hoody, a Montbell hooded synthetic puffy and a thin North Face puffy. No shell of any sort. We each had 3 pairs of gloves: an uninsulated pair, light weight ice leaders, and bigger gauntlet gloves. All of mine started out brand new. The middle pair is completely shot, and the two others are almost there.

Boots. That high and that cold for that many days really requires double boots. That much technical climbing really requires approach shoes. Anything in the middle is a compromise. In an example of Ian's simple genius, for routes this big he insists on similar equipment for each climber. "You're not taking gaiters? me neither". In this way, and because they may be the best climbing insulated boots available, we both ended up in silver La Sportiva Extremes. They're stiff and cumbersome for rock climbing and too thin to insulate well. Perfect. We clutzed around on the rock, but got it all done. I got frostbite, but only the last day. Perfect.

I took too much food, and Ian took just the right amount. Ian took 9.5 pounds and ate basically all. I took 14 lbs and finished with 3.75 pounds.

Everything we had weighed 82 lbs. Everything. As the weight-weenie thru-hikers say that's "From the skin out". Roughly 25 pounds of that was consumable. (food, fuel, rap tat). 20 lbs was group gear. (shelter, stove, climbing gear). Lots of ways of looking at the weight. But in the end, it wasn't much stuff. I don't mind the extra food and fuel. After a day and a half it was clear we had plenty of food and fuel. We could stretch to another night and still be stoked. And that's peace of mind if anything is.

Ridge climbs have a start and finish, and few other "rules". Touch summits, stay near the crest and you're good to go. Route finding variation will inevitably mean that each person's experience is unique. Some are better about staying on the ridge than others. Some touch more summits than others. To give a blow-by-blow of what we climbed and where the cruxes are would only mystify it all even further. In most cases the easiest, best, and most clear line is right along the divide. There are really only a few spots where one could and would divert. For instance, while traversing the section from North Palisade to Starlight we followed a route that I had never done before. I have done that traverse at least 10 times. And conditions this winter were different than I've ever encountered up there before. We stayed closer to the crest, but rappelled. Did we do better this time than I've done before? We stayed on the ridge? But we used what technically constitutes aid? Winchell's north ridge, same deal. North to south (and free solo in any direction) efforts in this section require significant deviation from the ridge. Like hundreds and hundreds of feet. Well, deviation or 5.11 crimpy free-soloing is required. But go south to north (as we did), and rappel a bunch and you can stay on the crest. It's a beautiful morass of variation and endlessly possible debate.

We snowshoed to South Fork Pass. Then climbed to a sweet campsite on the summit ridge of Middle Palisade later that day. Day 2 we climbed through the loosest section, past Norman Clyde Peak, over Mt. Williams and down to a sheltered camp between there and the start of the Palisade Crest. Day 3 we finished descending Mt. Williams and went through the entire Palisade Crest. We finished that section in the dark and camped on the flats of Scimitar Pass. Day 4 we did Jepson and Sill, and then the far more familiar terrain between Sill and Thunderbolt. We camped in the deepest dark faceted notch at the lower third of the NW ridge of Thunderbolt. Our fifth and final day we finished down to Winchell Col, up a sweet and circuitous route to Winchell's summit, then the countless ups and downs of Winchell's North Ridge. From Agassiz col we slogged in afternoon sun to the final peak. Perhaps our most tenuous down-climbing came in the wind-pressed upper reaches of the Agassiz-Winchell cirque on our exit. We tumbled and slid on firm snow down and down to the Thunderbolt tarn, and eventually Sam Mack Meadow. From Sam Mack to the main trail we wallowed, to waist and chest and deeper. On the main trail, some old tracks kind of supported our bare-booted passage. As we descended more and more tracks and less and less snow facilitated speedy transit.

All equipment and food we carried into the mountains. We made no caches beforehand. Yes, it is stylistically better. But I also think it is easier. The bulk of one's pack weight is equipment needed the entire time. Had we made a cache, or even 2 (therefore splitting the weight of consumables at best into thirds) we would have saved at most 8 lbs each. I don't think that is significant. By not stashing we could be more flexible with dates and other logistics. And we didn't have to risk avalanches and injury by slogging to the crest one or more times prior. So, say what you want about caching, but I think it would have just made the endeavor overall harder. We did temporarily abandon snowshoes at the base of south fork pass.

We started climbing the day we approached. Like the question or caching or not, I think this choice is ultimately one of efficiency. Good style in this case equals efficiency. Ian feels it is more in the stylistic realm. He insists we would be faster and more ensured of success on route if we camped at the start. But that car-to-car completion is becoming the norm and delivers a higher style performance. Perhaps, but weather and work windows are only so long. It is my opinion that spending full days on the move starting the moment one leaves the car is the safest and most efficient way to send something like this. Provided one is acclimated... In any case, we did what we did. We approached an attempt at the Evolution Traverse last winter with the same strategy. Maybe that worked against us there. This debate really comes to a head (at least betwixt Ian and I...) when discussing recording times. I've started compiling record times here. Most small endeavors are listed car to car. However, for some reason, I feel that these traverses should be down by on-route times. Ian disagrees. In either case, we have nothing to claim for this winter ascent. (Unless we start distinguishing by season and speed. Which I think is silly), but the debate, among the two of us that seem to care, "rages" on.

Alright. That's all I can think of for now. Pardon the dense reading and unedited style. I have a more literary, introspective piece written up, but I'm saving that for potential publishing elsewhere. I'll keep you posted.

Big thanks to rockstar romantic supporters, our primary employers (Sierra Mountain Guides and the American Alpine Institute), Tim Richards and Sterling Rope, and Evolv Sports and Designs.

Slovenian alpinist Marko Prezelj describes what he calls a "classic dilemma of modern adventure activities." When in the mountains with our cameras and satellites and sponsors and agendas are we "'living the moment' or 'capturing the moment'?" To be moving forward into life after an experience that one has described as "one of the greatest American mountaineering achievements" (whoa, exaggerate much, Bela?) is reassuring. I can't speak for Ian, but I constantly wrestle with my own motivations. Am I tackling these things in the peaks for recognition and accolades? Or for more "pure" rationale? The contentment I feel with taking on the rest of life confirms, to me, that the real value of our Palisade Traverse was in the moment; the opportunity to dig deep and work hard. Truth is, writing up any sort of logistics post has been directly requested a few times. And it's like pulling teeth to find the motivation to lay it down here. But here it is, this one's for you.

There are pictures and fluffy news articles out on the web now. I'll let you seek that out. There's video of us mumbling, exhausted, to the quirky and dynamic Skandar. I'll let you search that out. And make your own guesses about what, besides 63 lbs of body weight, Skandar might have lost there at 16k in the Karakoram. This post is unadulterated words. Stream of consciousness spray.

We trained like fools. As far back as the vernal equinox 2012, the day the rules changed that year, I can find an exchange between Ian and I. "Let's do something huge [next winter]. Let's pull smart and @&$#ing hard". I quit sugar and wheat for months at a time. Ian ran. I logged weeks on end of 40-60 hours of training volume, and went to the gym on days in town. Ian cut his drinking and body mass by pounds. Ian turned his sacred rocktober into rockandrun-tober. He woke early on normally casual mornings in Indian Creek to bust out intervals. I hear he even ran down bunnies for extra protein. We skied and scratched and post-holed all over the High Sierra through the early winter. We even risked life, limb and core-shot ropes for an obscure, and likely first, ascent.

We put our loved ones through stress. Modern communication technology allows for the option of emergency response in the hills. But Spot devices fail. We had a plan, we had a contingency, we had a contingency to the contingency, we had buy-in from our responsible people out in civilization. But when the Spot failed to deliver the messages we sent for a day, our ladies were not impressed. I have strong feelings about crafting an excellent emergency response plan for those we leave responsible in civilization. That is an entire post of its own, coming up.

We faced uncertainty. Pacing on summer efforts in the Palisades and elsewhere in the range, compared to winter pacing on the same endeavors indicated that the food and fuel we could carry in the Palisades might give us enough time to complete the whole deal. Weather forecasts beyond 5 days (What we determined to be our threshold for self-contained winter climbing of this nature) are not perfect. And we needed perfect weather. Ian did the entire traverse in summer and remembered certain sections as real burly. "What will we do there?" Not to mention all the "normal" issues: We had no extra gear to drop. We had no margin for injury. However, had you asked us beforehand, we'd have asserted that we had no margin for illness.

But we had illness. Ian toughed out some rugged lower gi distress on day 2. Food went straight through. Ian's built like a rail. A tough-as-nails, burly-ass rail. But a rail nonetheless. He gave up empty beer calories and carved pounds off his physique the weeks before. High altitude exertion stripped calories that day 2's poop-fest did nothing to replace. He bonked hard, but climbed harder. The dude wanted it, and has skills to back up the desire.

If Sierra ridges are some of the biggest and baddest around, Ian could very well be the biggest and baddest ridger around. Summer and winter, he's accumulated a ridge-running resume virtually unequalled. And he's not done. Sick f'er was already rattling off big dreams before we finished Agassiz. Its an honor to watch him weave high-level athleticism, skill, logistics and motivation into hard-charging accomplishments. I feel blessed to surf the swells of his perfect storm of ridge-line accumen.

I bring my own unique qualities. The coach in the gym, just today, said "you're real good at breathing." A tough-to-please mentor has pointed out that I "have become efficient in alpine rope handling techniques". I spend more time guiding high and rocky ridges than anyone else, at least here in the Sierra. I pushed limits last summer in the first guided ascent of the complete Evolution Traverse.

We carried very little. A Black Diamond tent sheltered us and the snow-melting stove. A tiny titanium jetboil and 20 oz of pressurized fuel melted snow, boiled water to hydrate meals, and warmed the occasional hot water bottle. We even heated the tent while preparing one morning. We finished with plenty of fuel. We each carried about 1/2 of a standard length foam sleeping pad. We carefully laid out the rope, slings and our backpacks beneath our feet each night. We shared Ian's 2lb Feathered Friends Spoonbill bag. The Spoonbill was clutch. It cut our sleeping insulation weight to about 40% of what it might have been otherwise. That's huge. Had we gone with traditional sleeping bags we each would have carried 2.5 lbs of down and nylon. Because the Spoonbill isn't insulated on the bottom and because we could share some body heat in the shared space, we were super comfortable with a tiny fraction of your standard two person sleep system. I can't recommend the Spoonbill highly enough. We packed it all in matching Cold Cold World Ozone packs. Good luck trying a modern, mass-produced, ultralight pack on a ridge like this. I've seen packs destroyed in a single route, but my Ozone now has 3 big traverses on it. It's about done, but I'm more than psyched with its durability.

Teams on previous attempts carried steel spikes for all eight appendages. That's roughly 8 pounds of steel that they had to put on and off and deploy and stow over and over again. We took a single 8 oz CAMP aluminum ice axe. We tread-milled through firm snow and ice, but didn't ever have to decide whether to spike up or not. Simple minds need simple decision-making. We gambled, and maybe won as a result.

On previous big traverses I've been stoked to carry a short, single-rated rope. 30 or 40m of 9.2 stows nicely over the shoulder, inspires confidence on sharp edges, deploys rapidly, and can be forced into function on most Sierra rappels. An 11th hour decision, aided by our generous contact at Sterling Rope, left us taking along 50m of twin rope. We immediately folded it in half and virtually never used it out of its 25m form. We worked it out, and were thankful for the extra length in a handful of rappels. Much thanks to Tim Richards and Sterling for the better-than-perfect Photon 7.8.

We wore light clothing. Long johns and softshell pants each. I carried lightweight CAMP wind pants and never wore them. We each did our own thing on the upper body. I wore a t-shirt, an OR fleece hoody, a Montbell hooded synthetic puffy and a thin North Face puffy. No shell of any sort. We each had 3 pairs of gloves: an uninsulated pair, light weight ice leaders, and bigger gauntlet gloves. All of mine started out brand new. The middle pair is completely shot, and the two others are almost there.

Boots. That high and that cold for that many days really requires double boots. That much technical climbing really requires approach shoes. Anything in the middle is a compromise. In an example of Ian's simple genius, for routes this big he insists on similar equipment for each climber. "You're not taking gaiters? me neither". In this way, and because they may be the best climbing insulated boots available, we both ended up in silver La Sportiva Extremes. They're stiff and cumbersome for rock climbing and too thin to insulate well. Perfect. We clutzed around on the rock, but got it all done. I got frostbite, but only the last day. Perfect.

I took too much food, and Ian took just the right amount. Ian took 9.5 pounds and ate basically all. I took 14 lbs and finished with 3.75 pounds.

Everything we had weighed 82 lbs. Everything. As the weight-weenie thru-hikers say that's "From the skin out". Roughly 25 pounds of that was consumable. (food, fuel, rap tat). 20 lbs was group gear. (shelter, stove, climbing gear). Lots of ways of looking at the weight. But in the end, it wasn't much stuff. I don't mind the extra food and fuel. After a day and a half it was clear we had plenty of food and fuel. We could stretch to another night and still be stoked. And that's peace of mind if anything is.

Ridge climbs have a start and finish, and few other "rules". Touch summits, stay near the crest and you're good to go. Route finding variation will inevitably mean that each person's experience is unique. Some are better about staying on the ridge than others. Some touch more summits than others. To give a blow-by-blow of what we climbed and where the cruxes are would only mystify it all even further. In most cases the easiest, best, and most clear line is right along the divide. There are really only a few spots where one could and would divert. For instance, while traversing the section from North Palisade to Starlight we followed a route that I had never done before. I have done that traverse at least 10 times. And conditions this winter were different than I've ever encountered up there before. We stayed closer to the crest, but rappelled. Did we do better this time than I've done before? We stayed on the ridge? But we used what technically constitutes aid? Winchell's north ridge, same deal. North to south (and free solo in any direction) efforts in this section require significant deviation from the ridge. Like hundreds and hundreds of feet. Well, deviation or 5.11 crimpy free-soloing is required. But go south to north (as we did), and rappel a bunch and you can stay on the crest. It's a beautiful morass of variation and endlessly possible debate.

We snowshoed to South Fork Pass. Then climbed to a sweet campsite on the summit ridge of Middle Palisade later that day. Day 2 we climbed through the loosest section, past Norman Clyde Peak, over Mt. Williams and down to a sheltered camp between there and the start of the Palisade Crest. Day 3 we finished descending Mt. Williams and went through the entire Palisade Crest. We finished that section in the dark and camped on the flats of Scimitar Pass. Day 4 we did Jepson and Sill, and then the far more familiar terrain between Sill and Thunderbolt. We camped in the deepest dark faceted notch at the lower third of the NW ridge of Thunderbolt. Our fifth and final day we finished down to Winchell Col, up a sweet and circuitous route to Winchell's summit, then the countless ups and downs of Winchell's North Ridge. From Agassiz col we slogged in afternoon sun to the final peak. Perhaps our most tenuous down-climbing came in the wind-pressed upper reaches of the Agassiz-Winchell cirque on our exit. We tumbled and slid on firm snow down and down to the Thunderbolt tarn, and eventually Sam Mack Meadow. From Sam Mack to the main trail we wallowed, to waist and chest and deeper. On the main trail, some old tracks kind of supported our bare-booted passage. As we descended more and more tracks and less and less snow facilitated speedy transit.

All equipment and food we carried into the mountains. We made no caches beforehand. Yes, it is stylistically better. But I also think it is easier. The bulk of one's pack weight is equipment needed the entire time. Had we made a cache, or even 2 (therefore splitting the weight of consumables at best into thirds) we would have saved at most 8 lbs each. I don't think that is significant. By not stashing we could be more flexible with dates and other logistics. And we didn't have to risk avalanches and injury by slogging to the crest one or more times prior. So, say what you want about caching, but I think it would have just made the endeavor overall harder. We did temporarily abandon snowshoes at the base of south fork pass.

We started climbing the day we approached. Like the question or caching or not, I think this choice is ultimately one of efficiency. Good style in this case equals efficiency. Ian feels it is more in the stylistic realm. He insists we would be faster and more ensured of success on route if we camped at the start. But that car-to-car completion is becoming the norm and delivers a higher style performance. Perhaps, but weather and work windows are only so long. It is my opinion that spending full days on the move starting the moment one leaves the car is the safest and most efficient way to send something like this. Provided one is acclimated... In any case, we did what we did. We approached an attempt at the Evolution Traverse last winter with the same strategy. Maybe that worked against us there. This debate really comes to a head (at least betwixt Ian and I...) when discussing recording times. I've started compiling record times here. Most small endeavors are listed car to car. However, for some reason, I feel that these traverses should be down by on-route times. Ian disagrees. In either case, we have nothing to claim for this winter ascent. (Unless we start distinguishing by season and speed. Which I think is silly), but the debate, among the two of us that seem to care, "rages" on.

Alright. That's all I can think of for now. Pardon the dense reading and unedited style. I have a more literary, introspective piece written up, but I'm saving that for potential publishing elsewhere. I'll keep you posted.

Big thanks to rockstar romantic supporters, our primary employers (Sierra Mountain Guides and the American Alpine Institute), Tim Richards and Sterling Rope, and Evolv Sports and Designs.

|

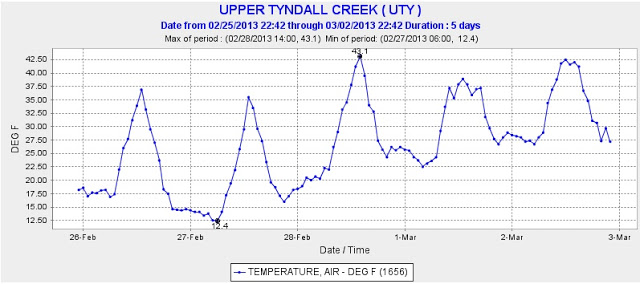

| Temperature graph for our dates at 11,400 feet well south of the Palisades |